Before We Dive In

Let me start with a confession.

Despite spending most of my career designing and architecting hyperscale networks, connecting clouds, carriers, data centers, and critical infrastructure around the world, subsea cables were never truly in my domain of expertise. I understood them quite well, sure. But I didn’t really know them, not the way I knew BGP and label switching architectures, large-scale network designs, routing convergence, or network observability and automation at scale.

That changed thanks to someone I’ve been lucky to call both a close friend and one of the most knowledgeable professionals I’ve ever worked with in this field: Rogerio Mariano.

Rogerio has dedicated a significant part of his career to subsea cable systems. Through his insights, shared across conversations, whiteboard sessions, and deep-dive discussions, I began to understand just how critical this often-invisible layer of infrastructure truly is, not just for cloud networking but for the modern Internet itself.

This article is, in many ways, the result of that learning journey. It’s a curated deep dive into the undersea world that powers our most visible platforms. It blends technical exploration with strategic context. It’s written for network engineers of all levels, whether you’re just getting started or you’ve been in the trenches for decades, because everyone working in modern connectivity needs to care about the ocean.

So, while I may not be a subsea engineer, I now understand why I should have been paying attention all along. And I hope that by the end of this read, you will too.

Let’s dive in.

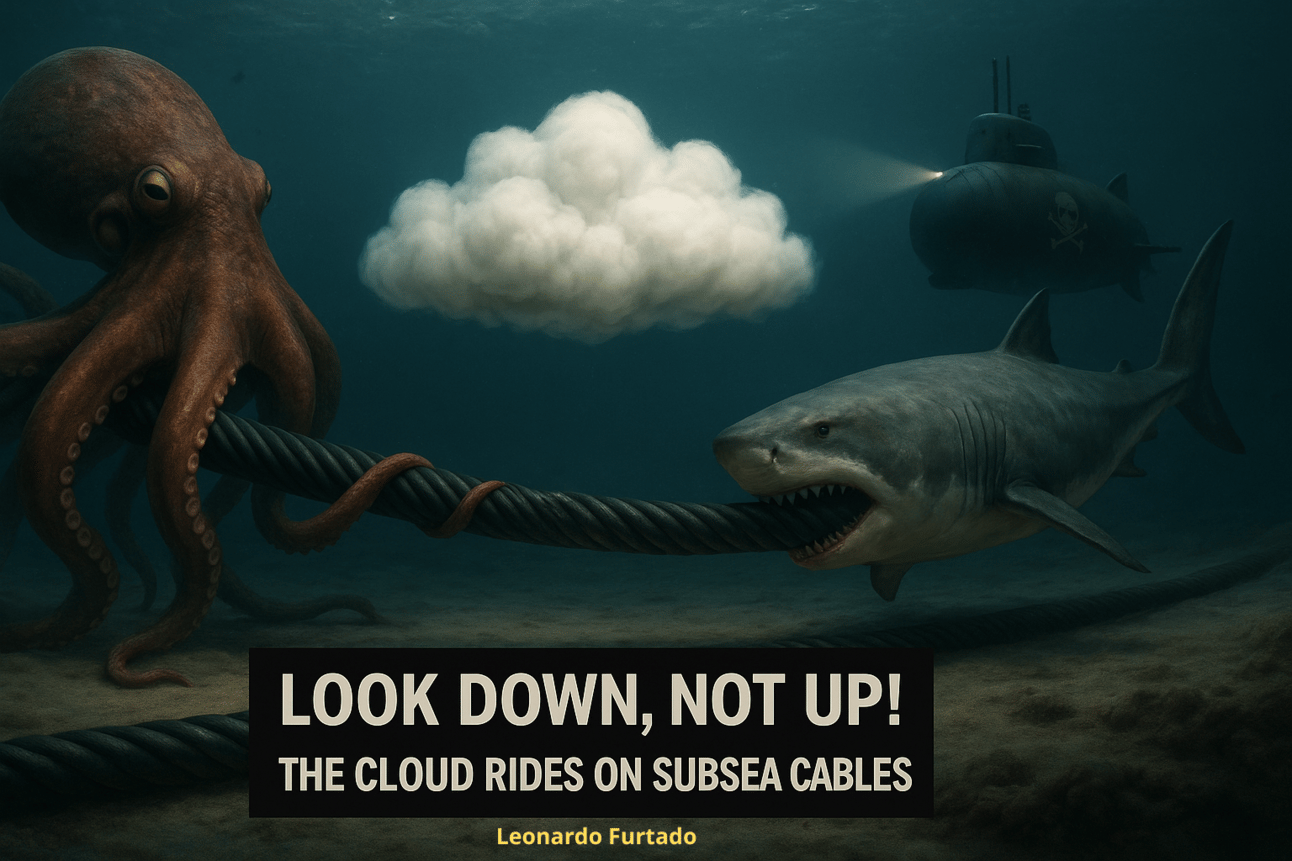

Look Down, Not Up

When most people hear the term “the cloud,” they instinctively look up.

It’s a comforting image: something weightless, soft, and invisible; data floating effortlessly in the sky. Many people imagine their photos, emails, video calls, and apps being transmitted by satellites in space, beaming their lives across continents from above.

But the truth is far wetter, darker, and stranger.

The real cloud, the physical infrastructure that underpins your every Slack message, your Netflix binge, your code commit, is not floating above your head. It’s sunk deep beneath your feet, resting quietly at the bottom of the ocean. The cloud rides on cables. Thousands of miles of them. Each thinner than a garden hose, yet pulsing with unimaginable amounts of data.

Subsea fiber-optic cables are the actual backbone of the Internet. They connect continents, cloud regions, and data centers with low-latency, high-bandwidth capacity that satellites simply can’t touch. In fact, more than 95% of all international Internet traffic is carried not through the sky, but along the seafloor, through these humble glass threads. Despite the sci-fi allure of space-based infrastructure, satellites currently account for only a tiny fraction of global data transfer. They remain essential for remote locations and emergency use cases, but are no match for the fiber-optic arteries that make up the true nervous system of the digital world.

This misunderstanding isn’t just a trivia question; it carries significant weight. If we imagine the Internet as weightless, untethered, and “in the sky,” we miss how dependent our digital lives are on extremely physical, fragile, and geo-politically charged infrastructure. These cables aren’t theoretical: they’re real-world engineering feats laid inch by inch across seabeds, subject to constant threats ranging from ship anchors and earthquakes to surveillance, sabotage, and legal jurisdiction.

The implications are vast. If one of these cables is severed, accidentally or otherwise, it can disrupt cloud services, sever financial markets, or disconnect entire nations from the global Internet. And yet, many technologists (including plenty of network engineers) rarely consider these cables unless there's an outage. The "invisible" layer of the Internet has become too easy to overlook.

But we shouldn’t overlook it. Especially not now.

As cloud providers scale globally, sovereign nations assert control over data flows, and latency-sensitive applications such as AI training, edge computing, and low-latency gaming demand ever faster and more reliable links, the role of subsea cables has never been more critical. They’re not just infrastructure. They’re leverage. They are geopolitical assets. And they’re a whole lot more fascinating than most people realize.

This article is a journey into the ocean, not to escape, but to gain a deeper understanding. We'll explore how these cables work, where they go, who owns them, what threatens them, and why you, as a network engineer, should start looking down more often than you look up.

Welcome to the deep end of the Internet.

How Subsea Cables Actually Work

It’s one of the greatest engineering feats you rarely think about: a thread of glass thinner than your pinky, stretched thousands of kilometers across the ocean floor, reliably carrying petabytes of data every second.

So how does it actually work?

At the heart of every subsea cable is light. Your data, whether it’s a video stream, a software update, or an encrypted chat, is broken into packets, encoded into light pulses, and sent at high speeds through optical fibers made from ultra-pure silica glass. These fibers are so clear and precise that light can travel through them for hundreds of kilometers before needing any boost. And the speed? Close to 200,000 kilometers per second, roughly two-thirds the speed of light in a vacuum.

But glass alone doesn’t cut it. A modern subsea cable is a multi-layered marvel of physics and materials science. Wrapped around the fragile core of optical fibers are layers of gel, copper, steel, and waterproof sheathing, all designed to protect it from the intense pressure, temperature changes, and external forces found in the ocean’s depths. Some cables are armored to endure rugged coastal environments or areas prone to fishing and shipping traffic. Others are left lighter and more flexible for deep-sea stretches where human activity is minimal.

To span the enormous distances between continents, these cables include optical amplifiers, often called repeaters, placed roughly every 50 to 100 kilometers. These devices regenerate the signal because even light fades with distance. Without them, a signal sent from New York would never reach London, let alone Singapore or Cape Town. Each repeater is powered by a constant electrical current running along copper conductors inside the cable, fed by high-voltage systems at the landing stations on shore.

These landing stations are the real-world endpoints of the cloud. Think of them as terrestrial gateways, where subsea infrastructure connects to metro fiber networks, long-haul terrestrial backbones, and ultimately into hyperscale data centers or Internet exchanges. Every packet that crosses an ocean must pass through a cable landing station.

Cables don’t just connect A to B. Many modern systems now use branching units, which allow a single main trunk line to offshoot into multiple destinations. Imagine a transatlantic cable branching into the UK, France, and Ireland from a single mid-ocean split. This improves efficiency and resiliency, and also raises questions about traffic segregation, security, and capacity sharing.

You might also hear the term fiber pairs. A typical subsea cable today can contain anywhere from 4 to 24 pairs of fibers, with each pair handling bidirectional traffic between two endpoints. With Dense Wavelength Division Multiplexing (DWDM), each fiber can carry dozens or even hundreds of channels, each using a different color (or wavelength) of light. The aggregate capacity of a single modern cable can exceed several terabits per second, sometimes even beyond 100 Tbps, depending on technology and fiber count.

But even with all this technology, faults do happen. And when they do, engineers rely on techniques like optical time-domain reflectometry (OTDR) to detect and localize breaks or degradations in the cable. Specialized ships are then dispatched, often days away, to fish the cable up from the seabed, splice or replace the damaged segment, and lower it back again. It’s slow, expensive, and highly dependent on weather and geopolitical conditions.

This isn’t plug-and-play infrastructure. It’s submarine surgery.

And yet, the entire Internet relies on it.

Every BGP route you announce across continents. Every CDN request that pulls from a different region. Every cross-region failover strategy or inter-cloud architecture you deploy. At some point, the bits flow through a cable lying on the ocean floor.

The more you understand about how these cables are built, how they operate, and how they fail, the better equipped you are to architect networks with real-world constraints in mind, not just theoretical topologies. These are not abstract links in a Visio diagram: they are physical lifelines to the global Internet.

Global Subsea Cable Landscape

Now that you understand how subsea cables work, it’s time to zoom out and see what you’ll see might surprise you.

Beneath our oceans lies a dense and growing network of fiber-optic highways, snaking their way across continents like digital veins. As of 2025, there are over 500 subsea cables in service or under construction, covering a combined distance of more than 1.4 million kilometers, enough to circle the Earth over 35 times. And yet, most people are unaware of their existence.

The layout is far from neat. These cables don’t run in tidy, symmetrical grids. Instead, they stretch in tangled loops, dog-legging around undersea mountain ranges, fault lines, and geopolitical chokepoints. If you looked at a map, you’d see a spaghetti-like mess of overlapping lines, clustered especially densely around the eastern U.S., western Europe, Southeast Asia, and key island hubs like Guam and Hawaii.

These are the intercontinental highways of the Internet, and they matter just as much, if not more, than traditional terrestrial backbones.

Strategic Routes That Shape the Internet

Let’s break down some of the most vital corridors:

Transatlantic (U.S.–Europe)

The oldest and most congested route. Cables like MAREA, Dunant, and Grace Hopper link Virginia, New Jersey, and the Iberian Peninsula with latencies often below 60 ms round-trip. This corridor carries immense volumes of cloud, financial, and media traffic.Transpacific (U.S.–Asia)

Connecting California to Japan, Taiwan, and Southeast Asia, this route is longer and more geologically volatile. Systems like FASTER, JUPITER, and Bifrost are modern efforts to expand capacity and diversify risk.Intra-Asia

The Asia-Pacific region has some of the highest cable densities due to population, cloud demand, and proximity of nations. This area includes the APG, ASE, and SEA-ME-WE cable families, many looping through Singapore, Hong Kong, and Japan.Africa and South America

Once underserved, now surging with investment. Google’s Equiano and Meta’s 2Africa cable systems are building new rings around the African continent. In South America, cables like ARBR and EllaLink now connect directly to Europe, bypassing U.S.-centric routing.Middle East and Indian Ocean chokepoints

Many global cables converge through the Suez Canal–Red Sea corridor or the Strait of Malacca. These are critical and vulnerable choke points for Internet resilience, where multiple cables pass through narrow, politically sensitive waterways.

Fun fact: Only a handful of small islands, like the Azores or Diego Garcia, serve as key relay points between continents. These island landing stations are essential to mid-ocean branching units.

From National Lifelines to Corporate Backbones

Historically, cables were deployed and operated by consortia of telecom providers from various countries. This model enabled cost-sharing, redundancy, and shared access to capacity among the different partners. But today, the landscape is shifting dramatically.

Tech giants, especially Google, Meta, Microsoft, and Amazon, are laying their own cables. Sometimes in partnership, but increasingly on their own terms. These companies seek guaranteed capacity, lower latency, improved reliability, and control over the physical path of their data. This new era of privately owned cables represents a strategic transformation in how the Internet is built and governed.

For example:

Google owns or co-owns over 20 cables, including Equiano, Dunant, and Curie.

Meta’s 2Africa project is expected to be the largest subsea cable system in the world, encircling the entire African continent.

Microsoft has partnered on MAREA, a transatlantic high-capacity cable that was one of the first to adopt open cable architecture.

The implications are profound. These corporations aren’t just renting capacity; they are becoming infrastructure owners. That changes the game when it comes to network control, availability, and performance at a global scale.

In the next section, we’ll examine the threats facing this hidden mesh of digital arteries, from trawlers and tectonics to geopolitics and espionage. While subsea cables might be resilient, they are not invincible.

Threats to Subsea Infrastructure

Despite their industrial-strength sheathing and oceanic remoteness, subsea cables are surprisingly vulnerable. In fact, the biggest danger to global connectivity is not a cyberattack, nor a failed data center, nor even solar flares: it's the frayed end of a fiber cable, somewhere deep underwater.

The threats facing subsea cables come from all angles: nature, humans, and geopolitics. Each one underscores a hard truth that network engineers must never forget: the global Internet is a physical system, and its weak points are often more mundane and more exploitable than we’d like to admit.

1. The Everyday Threat: Ships, Anchors, and Fishing Nets

Believe it or not, the leading cause of subsea cable damage is human activity, specifically, fishing and shipping. Anchors accidentally dragged across the seabed, bottom trawling nets, and careless maritime navigation are responsible for more than 70% of all cable faults.

These incidents are widespread near coastlines, where cables transition from deep water to shore. In these areas, cables are buried beneath the seabed using a technique called ploughing, but they can still be disturbed or unearthed by large ships operating outside designated safe zones.

These are rarely deliberate attacks. But they can have wide-reaching consequences.

For example:

In 2022, a fishing vessel damaged the SEA-ME-WE-5 cable near Egypt, disrupting Internet traffic between Europe and Asia.

In 2021, a subsea cable off the coast of Vietnam was damaged twice within a three-month period, resulting in widespread Internet slowdowns across the region.

The reality is that a few careless nautical decisions can throttle international bandwidth for millions of users.

2. Natural Hazards: Earthquakes, Landslides, and Tsunamis

The ocean floor is not a static environment. It shifts, heaves, and trembles, especially in seismically active regions, such as the Pacific Ring of Fire. Subsea cables must survive earthquakes, underwater landslides, and volcanic eruptions that can bury or tear them apart without warning.

One of the most striking examples occurred in January 2022, when the eruption of the Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha'apai volcano severed the only undersea cable connecting the island nation of Tonga to the rest of the world. For several days, the country was almost entirely cut off from the global Internet. Emergency communications relied on satellite backups, which were limited in capacity and range.

Other times, the threat is hidden. A cable might be damaged by a slow-moving landslide triggered by years of sediment buildup, only revealing its failure when latency spikes or packet loss appear in international traffic.

3. Espionage and Sabotage

Subsea cables are not just infrastructure: they’re intelligence goldmines.

In recent years, cables have become a focal point for covert surveillance and geopolitical sabotage. While many details remain classified, declassified documents have revealed that state actors, especially intelligence agencies, have long sought access to undersea communications.

The NSA’s FAIRVIEW and GCHQ’s Tempora programs, for instance, were reported to include monitoring data from landing stations and fiber taps. Subsea cable data is encrypted in most modern systems, but metadata and routing information remain sensitive. And in some older systems, encryption may not be robust or consistently applied.

On the sabotage side, tensions are rising. In 2021, Norwegian authorities investigated multiple severed cables linking their mainland to Svalbard, a strategic Arctic archipelago. In the Baltic Sea, unexplained ruptures of communication and gas pipelines have triggered alarm across NATO countries. Although the cause is often “inconclusive,” suspicions of deliberate interference loom large.

Russia, China, the U.S., and others are now openly planning military strategies for protecting (or disrupting) subsea infrastructure in times of conflict. The cables, once obscure, are now acknowledged as high-value targets.

4. Legal Jurisdiction and Control

A more subtle, yet no less profound, threat comes from law and policy.

Subsea cables often cross dozens of Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs), maritime regions where countries have jurisdiction over natural resources and infrastructure. To lay or maintain a cable through these zones, operators must obtain permission, comply with local regulations, and sometimes collaborate with governments that have divergent political agendas.

This creates friction. In some cases:

Authoritarian regimes may deny permits or demand access to surveillance.

Disputes over maritime borders can delay or derail cable projects.

“Kill switch” clauses have been proposed by some governments, allowing them to force termination of cable access during national emergencies.

Even private tech companies that operate their own cables can face resistance. Governments increasingly want guarantees of sovereignty, data localization, and compliance with national security laws before they allow foreign-owned cables to land on their shores.

The Fragile Foundation of Resilience

Every one of these threats, whether natural, accidental, or intentional, has the potential to disrupt international connectivity. And while multiple redundant cables serve most major regions, the cost and time to repair a fault are measured in millions of dollars and numerous weeks.

Cable repair ships are few and far between. Obtaining permissions to operate in foreign waters can be a slow process. And every day, a major cable is offline, global routing tables shift, BGP paths reroute through less optimal links, and your cloud performance degrades in ways most observability tools won’t clearly show.

In short, the ocean is not a quiet place. And subsea cables are not invincible.

Next, we’ll explore how ownership and control of these cables are evolving, and why private tech companies, cloud providers, and national governments are now racing to claim their stake in this underwater battlefield.

Ownership, Control & Strategic Shifts

Once upon a time, the subsea cable industry was primarily the domain of national telecommunications carriers and international consortia. Cables were expensive, complex, and politically sensitive to deploy, so multiple countries and providers would band together to share the cost, the bandwidth, and the risk. Each partner would purchase a share of capacity, known as IRUs (Indefeasible Rights of Use), and gain access to the global infrastructure through collective ownership.

But the last decade has flipped that model on its head.

Today, the world’s largest tech companies, Google, Meta, Microsoft, and Amazon, are not just renting capacity. They’re building the cables themselves.

This shift has radically altered the power dynamics of global connectivity. Hyperscalers have realized that to guarantee performance, control costs, improve security, and deliver seamless experiences across continents, they cannot rely on shared or third-party infrastructure. Owning the cable means owning the experience.

The Rise of the Corporate Subsea Empire

Let’s take a few examples to understand how aggressive this trend has become:

Google has invested in more than 20 subsea cable systems, including:

Dunant: a transatlantic cable linking the U.S. and France, delivering 250 Tbps capacity.

Equiano: connecting Portugal to South Africa with branching units to West African nations. It supports Africa’s surging cloud demand and bypasses traditional European routing chokepoints.

Curie: linking Chile to Los Angeles, giving Google an edge in South American latency and sovereign cloud strategy.

Meta is spearheading the 2Africa project, expected to become the largest subsea cable project in history, encircling the African continent with over 45,000 kilometers of fiber. The project will serve more than 30 countries and is designed to reduce latency and increase bandwidth in underserved regions significantly.

Microsoft co-funded MAREA, a high-capacity transatlantic cable laid in partnership with Facebook and Telxius. This was also one of the first major cables to support open cable systems, allowing each partner to use different hardware vendors at each end, a move toward disaggregation in transport.

Amazon Web Services (AWS) has remained relatively quiet, but is steadily expanding its footprint with investments in private backbones and co-investments in cables to support its global infrastructure regions.

These companies are no longer just cloud providers; they are infrastructure operators, controlling the physical terrain over which global traffic flows. And this is about sovereignty, compliance, and strategic influence, along with performance.

Shifting Models: From Consortia to Ownership

Traditionally, a cable might have had a dozen owners from multiple countries. However, single-entity ownership is becoming increasingly common. The result? Private clouds that are truly private, end-to-end.

This allows hyperscalers to:

Deploy traffic engineering tailored to their services (e.g. prioritizing live streaming, model replication, or inter-region object storage).

Bypass congested or politically sensitive routes.

Ensure data sovereignty compliance by keeping traffic within controlled paths.

Integrate with their own monitoring, automation, and AI-based failure detection systems.

Furthermore, hyperscalers are also leasing capacity to others, effectively becoming service providers themselves. In some cases, they even compete with traditional telcos in the transit and CDN markets.

⚠️ But this shift raises serious questions:

What happens when vital infrastructure is controlled by corporations with no legal obligation to provide universal access?

How do governments regulate cable systems that aren’t run by carriers, but by cloud giants?

And in a time of rising geopolitical tension, who gets to decide which countries or companies can land a cable?

Government Response: From Passive to Proactive

Governments are no longer standing on the sidelines. As it becomes clear that subsea cables are not just telco assets but critical national infrastructure, policies and military strategies are evolving fast.

The European Union has issued guidelines to classify subsea cables as essential infrastructure, encouraging joint monitoring efforts and faster incident response coordination.

NATO has explicitly acknowledged the strategic importance of undersea cables and is exploring defense strategies to deter or respond to tampering, especially around the Arctic, the Baltics, and Atlantic chokepoints.

Countries like India, Brazil, and Saudi Arabia are funding or co-building cables that bypass traditional routes, offering redundancy and independence from U.S.-centric paths.

China is investing heavily in its own global cable initiatives, like Peace Cable, creating alternative corridors to Europe, Africa, and Southeast Asia—routes where Western countries may have little or no control.

In this new era, the question is not just “who connects to whom?” but “who controls the connection?” Every landing point, every route choice, every ownership stake has the potential to tip the balance in trade, surveillance, or warfare.

Subsea cables were once technical footnotes; now, they are digital battlegrounds, corporate leverage points, and national security concerns. Understanding who owns what, and where, is no longer the job of a lawyer or diplomat. It’s the job of every cloud architect and network engineer who wants to build globally resilient systems.

Up next: we’ll explore how new technologies, ranging from AI-powered monitoring to open cable systems and programmable subsea transport, are helping us build a brighter, more resilient future beneath the waves.

New Tech in the Deep

Subsea cables might sound like relics of the telegraph era, long wires laid across oceans, subject to the forces of anchors, pressure, and time. But today’s cable systems are nothing like their ancestors. They are smarter, faster, and more autonomous than ever before, infused with cutting-edge technology designed to maximize capacity, accelerate detection, and adapt to the ever-growing demand of cloud-scale workloads.

This transformation aims to deliver speed, resilience, automation, and architectural flexibility.

Dense Wavelength Division Multiplexing (DWDM): A Spectrum Renaissance

The amount of data a single optical fiber can carry has exploded over the past two decades, thanks to DWDM, which enables multiple signals, each using a different wavelength (or color) of light, to be transmitted simultaneously over the same fiber.

Modern subsea systems often support up to 96 or even 120 wavelengths per fiber, each capable of handling 100G or 400G channels, pushing total capacity per cable into the multi-terabit range. Some systems today advertise total design capacities over 150 Tbps, and new designs are aiming for even more.

The key to this explosion? Better transponders, more intelligent error correction, and advanced modulation schemes like 16-QAM and probabilistic constellation shaping (PCS), which pack more bits into each optical signal without increasing power or sacrificing distance.

This is a capacity and engineering story. Pushing more data over fewer fibers reduces cost, increases ROI, and allows providers to do more with each landing station.

Open Cable Systems: Disaggregation Beneath the Waves

Traditionally, subsea cable operators would purchase end-to-end systems from a single vendor, comprising cable, amplifiers, repeaters, and transponders all bundled together. But just as we’ve seen disaggregation in data centers and WAN infrastructure, a similar revolution is underway underwater.

Open Cable Systems decouples the submerged plant (cable, repeaters) from the terminal equipment (modems, transponders). This gives operators, especially hyperscalers, more control over upgrades, vendor selection, and integration with their terrestrial networks.

For example, Google or Meta might deploy subsea fiber designed by one vendor but connect it to transponders from another, optimized for their particular cloud workloads or peering strategies. They can tune for latency, power, spectrum efficiency, or even machine learning workload replication patterns.

This flexibility is particularly useful in supporting multi-tenant designs, where multiple operators or organizations share the same physical cable but manage their own endpoints independently.

AI and Real-Time Telemetry: Watching the Water

Modern cable systems aren’t just fast: they’re increasingly self-aware.

New generations of cable monitoring platforms use AI-powered fault detection and telemetry correlation to pinpoint anomalies faster than ever. Using optical reflectometry, signal analysis, and machine learning, they can detect:

Signal degradation from repeaters or aging fiber

Potential intrusion or tampering based on sudden impedance shifts

Latency or jitter changes hinting at environmental impact (e.g., temperature shifts, seismic activity)

These platforms help operators isolate faults with greater precision, reducing the mean time to repair (MTTR). Instead of weeks of uncertainty while a ship is dispatched, systems can pre-localize the problem and even simulate repair strategies based on past events.

There’s also a new trend: leveraging undersea cables themselves as sensors. Some projects are experimenting with using cable vibrations and optical backscatter to detect underwater earthquakes, currents, or even nearby ship movement, turning passive infrastructure into active ocean observatories.

Programmable Transport and Dynamic Spectrum Sharing

The next frontier in subsea architecture is dynamic spectrum allocation, essentially treating fiber capacity as a shared resource pool that can be sliced, moved, and adapted in near real-time.

In this model, operators can:

Allocate bandwidth dynamically to cloud regions or countries based on demand.

Shift capacity away from congested or degraded routes.

Apply software-defined constraints to comply with data sovereignty rules (e.g., ensuring EU traffic doesn’t leave EU-controlled fibers).

This is especially powerful when paired with SDN-like control planes for transport networks. Some subsea operators are now exposing network APIs or telemetry feeds directly to their largest tenants (often cloud providers), allowing them to react to subsea conditions in tandem with their terrestrial routing, CDN placement, or failover decisions.

Think of it as Subsea-as-a-Service: programmable, flexible, and deeply integrated into the global cloud control plane.

Fiber Pair Innovation and Branching Topologies

As demand increases, cable systems are shifting away from monolithic point-to-point designs. New builds incorporate:

Higher fiber pair counts: Instead of 6–8 pairs, new cables often support 12, 16, or even 24, allowing for tenant isolation or dedicated cloud-region interconnects.

Branching units: These are like underwater routers, nodes that split the cable to multiple destinations. For example, one main trunk might go from Portugal to South Africa, with branches to Nigeria, Angola, and Namibia along the way.

Reconfigurable Optical Add/Drop Multiplexers (ROADMs): Although rare in subsea systems today, ROADMs are being explored for specific regional applications to offer greater path diversity and dynamic routing underwater.

These features not only improve capacity, but they add resiliency, topological flexibility, and multi-region scalability, critical traits for hyperscale and sovereign infrastructure.

The subsea world is no longer static. It's evolving rapidly, mirroring the trends we see above ground in SDN, automation, observability, and open infrastructure. But it’s doing so in a realm where repair takes weeks, hardware must survive for 25+ years, and mistakes can cost millions.

Understanding these technologies isn’t just a curiosity; it’s a necessity for anyone architecting modern, global networks. Because what happens 8,000 meters beneath the ocean can make or break your next cloud failover… or your Friday night Netflix stream.

Why Network Engineers Should Care

For many engineers, subsea cables exist somewhere in the mental background, interesting trivia, maybe, but largely abstract. After all, we don’t configure them. We don’t log into them. We don’t troubleshoot them with show commands.

But that mental model is increasingly obsolete.

Whether you're managing global transit policies, building cloud-native apps, optimizing CDN placement, or designing inter-region failover, the truth is this: you depend on subsea cables more than you think.

Let’s bring this home.

Your BGP Routes Ride the Ocean Floor

Every time you announce prefixes to an upstream ISP or receive a default route from a cloud edge, you're inheriting a set of assumptions: bandwidth, latency, resilience, reachability.

But how often do you ask where those packets physically travel?

Consider this: traffic between your users in São Paulo and an API endpoint in Frankfurt may take radically different paths depending on which cable system your provider prefers. One may run through the U.S., the other directly from Brazil to Europe via the EllaLink cable. The difference? Nearly 40 milliseconds of latency, and wildly different exposure to geopolitical chokepoints or single points of failure.

Now multiply that across dozens of APIs, services, and regions. The physical path matters.

If your cloud workloads rely on inter-region replication (think: AI model updates, database syncs, multi-region K8s clusters), then latency and throughput across subsea links can make or break performance and cost. Understanding cable geography is foundational.

The Illusion of Redundancy

Designing for high availability? Great. You’ve got dual carriers, dual regions, maybe even diverse IX peering.

But redundancy is only real if the underlying paths are physically diverse.

Time and again, engineers discover that “diverse” IP routes share the same subsea cable. Or worse, that multiple upstreams are buying capacity from the same cable operator, on the same fiber pairs, with no visibility into the underlying design.

This happened in 2022, when two major cables serving Taiwan were damaged days apart, knocking out primary and backup links for entire network segments. The routing looked redundant. The seabed wasn’t.

If you’re designing mission-critical or sovereign workloads, don’t just ask “who’s my upstream?” Ask what cables they ride on, and where their landing stations are. Tools like submarine cable maps, latency monitoring, and traceroutes are your friends here.

Cloud Design Must Meet Physical Constraints

Cloud providers may abstract away the cable layer, but you can’t afford to ignore it.

When you select a primary cloud region and a disaster recovery region, your RTO and RPO aren’t just about database replication speeds: they’re about physics. What’s the latency across the chosen path? What if that subsea cable is congested or out of service? Can your architecture tolerate a 200ms round-trip in failover mode?

If your services operate globally, with users, APIs, or data distributed across continents, you need to model inter-region dependencies not just logically, but geographically.

It’s not enough to say “multi-region.” You have to say “multi-path,” with paths that ride different oceans, different operators, and ideally, different geopolitical territories.

Observability Tools Hide the Ocean

Most network observability platforms, NetFlow collectors, packet brokers, SASE dashboards, or cloud telemetry tools don’t show you the subsea layer. They might show you ASN hops, RTT graphs, or packet loss heatmaps. But they rarely say: “This packet traversed MAREA. This failover crossed SEA-ME-WE-6.”

This absence can breed overconfidence.

The Internet is full of smart routing, yes. But it's also full of opaque dependencies, undocumented vendor arrangements, and brittle shared infrastructure. Without deep visibility, you're flying blind across oceans.

That’s why many hyperscalers now integrate subsea-aware routing telemetry into their infrastructure control planes. They know that packet delay isn’t just a BGP blip, it’s a ship anchor, a repeater failure, or a cable being repaired off the coast of Guam.

Security, Compliance, and Sovereignty Are All Subsea Questions

Lastly, there’s the compliance elephant in the room.

If you work with industries subject to data residency, national sovereignty, or cross-border transfer regulations, you must understand how and where your traffic flows. Just because your cloud provider says “EU region” doesn’t mean your packets never leave the EU.

In specific configurations, routing policies, DNS resolution paths, or third-party dependencies can route data through non-compliant cables, exposing your workloads to legal or audit risk.

In high-security environments, like financial services, defense, or healthcare, you should go a step further: demand your provider discloses landing station geography, cable routes, and capacity sharing models. You can’t secure what you don’t understand.

From Invisible to Strategic

Network engineers are trained to think in OSI layers. Subsea cables don’t appear in any of them: not explicitly, anyway. But maybe it’s time we expand our mental models.

These cables are the layer zero of the global Internet. They shape routing outcomes, failure domains, and latency profiles. They affect your observability, your redundancy, and your legal compliance. And they are increasingly becoming strategic assets, wielded by both tech companies and nation-states.

So if you’re serious about designing globally resilient networks, don’t just look at the diagram in your NMS. Don’t just check the AS paths on your BGP table.

Look at the ocean. It’s where your packets go. And it’s where the future of networking is increasingly being decided.

The Cloud Is Wet. Period.

We began with a simple challenge to perception: when you hear “the cloud,” don’t look up: look down.

What started as a metaphor has revealed itself as an urgent reality. The digital world we rely on daily, our messages, meetings, backups, models, and media, isn’t hovering in the sky. It’s pulsing through thousands of kilometers of fiber-optic cable, lying silently on the seabed, wrapped in steel and gel, crossing tectonic boundaries and geopolitical minefields.

Subsea cables are the physical substrate of everything we call “online.” They’re not mystical. They’re engineered. Finite. Vulnerable. And absolutely essential.

Over the past decade, we’ve watched as hyperscalers turned from consumers of bandwidth to builders of infrastructure, owning the ocean routes that feed their clouds. We’ve seen nations scramble to protect cables like sovereign borders. We’ve seen outages that take entire countries offline, and quiet tensions beneath the waves that mirror the conflicts above.

Yet despite all of this, for many in the networking and cloud communities, subsea cables remain invisible. Abstracted and forgotten.

This article was an invitation to reverse that.

Because we can’t design resilient systems without understanding where they’re vulnerable, we can’t talk about global architecture without accounting for global infrastructure. We can’t build reliable routing, security, or compliance strategies while ignoring the very paths our packets take.

Subsea cables deserve a place in our mental models, not as curiosities, but as critical components of our stack.

Therefore:

If you build networks, you must learn the geography of global cables.

If you design cloud systems, you must model the physical realities beneath abstraction.

If you care about latency, privacy, sovereignty, or security, you must look at the ocean.

Because the future of the Internet is way more than just protocols, software, or clouds.

It’s about who owns the path.

Who protects it.

And who gets to use it when the world is watching.

Welcome to the real cloud. It's wet. It's wired. And it's more important than ever.

Once again, huge thanks to Rogerio Mariano for making my exploration of this complex universe so insightful and enjoyable! Make sure to follow him on LinkedIn!

See you in the next high-signal edition!

Leonardo Furtado